The Truth About

Jewish Assets In Iraq

by Professor

Yehouda Shenhav of Tel-Aviv University

"Jewish assets

in Iraq were ex-propriated twice, once by Iraq and then by

Israel"

Between 1948 and

1951, Israel faced two analogous demands. First, it was implored

to compensate Palestinians who had become refugees as a result

of the War of Independence, and whose property had been nationalised

by the General Trusteeship of the State of Israel. Second,

Iraqi Jews and their representatives in the Israeli government

- Minister of Police Bachor Shitreet was the most prominent

- were pressed for compensation for the assets they had left

behind in Iraq.

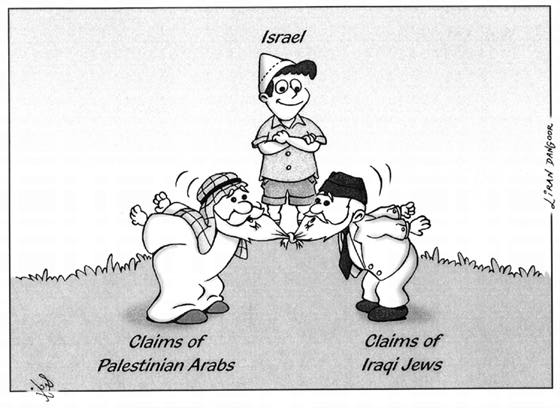

My study aimed

to show how Israel established a connection between these

two demands, and then freed itself from both of them.

Ultimately, Israel justified its refusal to compensate the

Palestinians on the grounds that the Iraqi Jews had also suffered

deprivations, and urged the Iraqi Jews to demand restitution

from Iraq.

Zionist activity

in Iraq began during World War II. But it was only at the

war's conclusion, when the dimensions of the Holocaust became

known, that the Iraqi Jewish community was considered a potential

alternative source for increasing the Jewish population of

Palestine.

The Jewish community

within Iraq was not Zionist-oriented, as the emissaries soon

discovered. As an overwhelmingly bourgeois community, the

Iraqi Jews understood the danger that Zionism posed to their

political, social and economic status. Those Jews who did

leave the country generally settled in Europe, India, Iran

and North America - as well as Palestine.

By 1947, however,

Iraqi Jews found themselves in an increasingly untenable position.

The aggressive activities of the Zionist movement, followed

by the birth of Israel, led many Arabs to associate all Jews

with Zionism. At the same time, nationalism was on the rise

in Iraq, marked by a distinct anti-Zionism.

The question of

the fate of Iraqi Jewry came up repeatedly in meetings of

the Israeli cabinet, most often on ShitreetĖs initiative In

September 1949, for example, Shitreet proposed a "transfer"

of Palestinian refugees and Iraqi Jews. Sharett and Prime

Minister David Ben-Gurion were unwilling to discuss the idea,

and dismissed Shitreet reproachfully.

In mid-October

1949, the Israeli press began reporting that Iraq was willing

to agree to a transfer, and there was evidence that senior

Iraqi officials supported such a move. But Ben-Gurion and

Sharett chose to ignore these signals, and despite Israel's

professed interest in absorbing Iraqi Jews, the two leaders

adopted an intransigent position. Ben-Gurion told the cabinet

that "all this talk about exchange seems very curious to me.

Clearly, if the Iraqi Jews could get out, we would never think

about asking for any type of exchange, whether of persons

or of property!"

Ben-Gurion and

Sharett were well aware of the hefty price Iraq would demand

for concluding any concrete agreement. Israel would have to

either repatriate the Palestinian refugees or compensate them.

In March 1950,

the Iraqi government passed a bill allowing Jews to renounce

their Iraqi citizenship, and to leave the country. Known as

the de-nationalisation law, it was to remain in effect for

one year and carried no stipulation about property.

A month after

passage of this bill, Israel made its first attempt to recover

Jewish assets from Iraq. The Government was willing to examine

the possibility of exchanging Arab property in Israel which

has not been abandoned for the property of Jews in Iraq. The

investigation, it was stressed, relates only to Iraq and not

to any other Arab country, and only to property which has

not been abandoned."

The plan proposed

by Ben-Gurion and Sharett called for nothing less than the

deliberate transfer of Israeli Arabs. Lief, the adviser for

land and border affairs at the Prime MinisterĖs Office, had

already begun to implement it. According to Uzi Benziman and

Atallah Mansour, in their book, "subtenants," Leif wrote to

the prime minister, the foreign minister and the treasury

minister that "as a first measure, I would instruct our representatives

in Paris to establish contact with members of the Iraqi Jewish

community in order to convince them to cease selling their

assets at reduced prices, and to signal that there is a chance

they will be able to obtain a higher price on the basis of

mutuality."

All efforts at

mediation failed, however, and the assets of Iraqi Jewry were

never brought to Israel. Nor did anything ever come of the

transfer plan.

In 1951, Zionist

activists were hard at work in Iraq. Some 35,000 Jews had

already departed, and another 105,000 were registered to leave.

Delays in the operation were caused not by Iraq but by Israel,

and specifically by the quota system then applied by the Jewish

Agency. On March 10 of that year, Iraq's prime minister proposed

a bill at freezing the assets of all Jews who had renounced

their citizenship. In order to prevent last-minute transactions,

the Iraqi treasury ordered the banks to close in the three

days before the law took effect. Jewish homes were searched,

their stores were closed and their cars and property impounded.

Sharett asked

his fellow cabinet members to consider Israel's response to

the Iraqi actions. "The question arises as to what, exactly,

we can do. Appeals can be sent to Britain and the United States,

of course ..... I assume that they will refuse to intercede

..... They can say "you took the property of the Arabs

who left Israel, you gave the property to the Trusteeship.

The Iraqis are doing the same thing..."

In the same discussion,

Sharett reported that some Iraqi Jews in Israel were calling

on the government to impound Arab assets in Israel and distribute

them to the Iraqi Jews. The majority of the cabinet agreed

that the transfer of Arab assets to Iraqi Jews was not feasible.

In its place,

Sharett proposed an alternative. "We declare that the entire

subject of Iraqi Jewish assets will be taken into consideration

in the final settlement, in determining compensation for the

Palestinians," he explained. "Since we have yet to abandon

the principle of paying compensation, we will now say that

the value of the Iraqi assets will be deducted from them."

Inventive as it

was, Sharett's idea did not satisfy Shitreet. He continued

to press for a tangible measure to ease the Iraqis' plight.

"The Iraqi Jews will come to the Foreign Ministry and ....

they will not be content with empty words," he told Sharett.

"There can be no doubt that their claim to Arab assets is

well-founded. Their situation is the direct result of the

creation of the state of Israel, and we have to consider a

way of compensating them from the Arab assets.

Kaplan retorted

that by the same token, it might be said that Israel should

compensate every individual who comes here. Poland takes the

Jews' money as well..."

The Knesset ultimately

approved the government's position on the Iraqi situation,

so that linkage between Iraqi Jewish property and Palestinian

compensation became Israeli policy.

"By expropriating

the assets of tens of thousands of Jews who immigrated to

Israel," Sharett said in a speech before the Knesset on March

19, "the Iraqi government has incurred a debt to the state

of Israel. Such a debt already exists between Israel and the

Arab world, and that is the debt of compensation to those

Arabs who left Israeli territory and abandoned their property.....

The action now taken by the Iraqi kingdom..... compels us

to link the two debts .... The value of the Iraqi Jewish assets

that were expropriated will be taken into consideration when

calculating the compensation we committed to pay Arabs who

abandoned their property in Israel."

This decision

to link the two "debts" treats Iraqi Jewish capital as a national

rather than a personal possession. In essence, that capital

was expropriated twice, once by Iraq and then by Israel. In

a memorandum sent to the UN Palestine Conciliation Commission,

the Foreign Ministry reaffirmed its commitment to compensating

the Palestinians, but added that "we cannot fulfil this commitment

if, in addition to bearing the burden of immigrant absorption,

Israel must provide for the restitution of 100,000 Iraqi Jews.

"In other words, had the Iraqi government not impounded Iraqi

Jewish assets, Israel could have compensated the Palestinians.

During the debate

that followed Sharett's speech, Knesset members took turns

denouncing Baghdad's action. Many representatives likened

it to steps taken by the Nazis. Meir Argov of Mapai said that

"Israel had been willing to do its share for the refugees,

but now, after this robbery of Iraqi Jews, Israel is released

from its obligation."

Sharett's speech

served to satisfy Iraqi Jews' demands for a concrete response

to Baghdad, and kindled hopes for a speedy restitution. In

a telegram to Israel, Zionist activists in Iraq wrote, "the

Jews now believe that they have something to depend on...

Jews whose assets have been frozen have approached us asking

whether they will have to show proof of those assets once

they arrive in Israel and, if so, how might such proof be

conveyed. "Naim Sofer, chairman of the organisation "Movement

of Iraqi and Eastern Jews in Israel," called on Israel to

implement its decision immediately. His initiative clearly

demonstrates the degree to which Iraqi Jews believed they

would receive compensation from Arab assets held by the Trusteeship.

Sofer's letter

served as a warning for the Foreign Ministry. While lower-level

officials assured Sofer that "the fate of Iraqi Jewish assets

is a constant concern for the government of Israel," the ministry's

upper echelons were already acting to avert a catastrophe.

"The frozen Iraqi Jewish assets may be registered," reported

one Foreign Ministry memorandum to the Prime MinisterĖs Office,

"but their sole purpose will be to deduct the value of those

assets from the amount of compensation to be paid for the

abandoned Arab assets." The memorandum added that the government

could not compensate the Iraqi Jews "without opening the gates

to a flood of private requests from tens of thousands of Arab

refugees who once owned assets of one kind or another in Israel."

Though Sharett

had always opposed the notion of transfer, the freezing of

Iraqi Jewish assets offered him a golden opportunity to free

Israel from Palestinian claims for compensation. And indeed,

almost as soon as the 120,000 Iraqi Jews arrived in Israel,

the government turned its back on them. The Foreign Ministry

objected to the creation of a special office to oversee the

registration of claims against Iraq for assets left behind.

According to historian Moshe Gat, Sharett insisted that "the

value of the Jewish assets impounded by Iraq would be tallied

when the question of compensation comes up for discussion.

That has yet to happen, and there is no telling when it will.

The issue remains hypothetical."

Hypothetical though

it was, the policy of linkage was twice put to the test. In

1955, a public committee was set up to register the claims

of Iraqi Jewish immigrants. The committee completed its work

in December 1956, and submitted its final report to the Foreign

Ministry. There it remained, unattended. The reason for the

ministry's inaction again was rooted in the linkage policy,

as indicated by documents relating to the committee. As one

internal memorandum advised, "It is recommended that we refrain,

at least for the time being, from declaring that the purpose

of the claims registration is to deduct the amount from that

of the compensation for abandoned Arab assets."

The second test

of the policy came in 1979, during peace talks between Israel

and Egypt. Addressing the Knesset, Shlomo Hillel asked Prime

Minister Menachem Begin about compensation for Iraqi Jews.

"The problem of Jewish property that was stolen by Arab countries

- and not just one Arab country - was raised and will be raised

in all our discussions, "Hillel quotes Begin as saying. "It

was raised and will be raised in all our discussions with

Egypt. That is why we agreed to create a committee to consider

the claims of all parties. When the right day comes, we will

submit our claims for assets seized illegally."

The peace treaty

with Egypt was signed, but no action was ever taken on the

Iraqi assets. Though it had linked the two claims, Israel

never offered compensation to either the Palestinians or the

Iraqi Jews. The linkage policy represents an historic milestone

for Israel and its attitude towards both the Palestinian refugees

and the Iraqi Jewish community. After their expropriation

by the Iraqi government, Jewish assets were then nationalised

by the state of Israel. Proof of that nationalisation can

be found in the Israel State Archives, in the files labelled

"Defence of Israeli Assets." Once it had claimed those assets

as its own, Israel could put them to any use - rhetorical

symbolic, or legal - it chose.

During the 1948

war, many Arab assets were either abandoned or seized. The

value of these assets has never been determined, but is probably

in excess of $5 billion. Israel, however, remains opposed

to paying that compensation as long as Jewish claims against

Arab states remain unsettled. The linkage policy stands unchallenged.

The linkage between

Palestinian and Iraqi Jewish claims grew out of the cynical

Israeli belief that Arab and Jewish interests are inherently

irreconcilable. In looking for the roots of the antipathy

between the Arabs and the Jews from Muslim countries - an

immense topic that lies outside the scope of this article

- one cannot ignore the way in which the Zionist movement

and later the Israeli government helped spawn those tensions.

From Ha'aretz

Magazine. April 10, 1998

Scribe:

The Israeli Government has explained its position concerning

Jewish assets in Iraq, of not compensating Iraqi Jews out

of the frozen Palestinian assets, by saying that the State

of Israel spent billions in resettling Iraqi immigrants in

Israel. WOJAC was just a camouflage.

What about the

assets of Iraqi Jews who did not go to Israel?

If

you would like to make any comments or contribute to The

Scribe please contact

us.

|